Updated on June 4, 2025: The Oklahoma legislature united to override Gov. Kevin Stitt’s veto on a bill allowing state funding for the OSBI’s Office of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons. The state’s House of Representatives overrode Stitt’s veto on HB-1137 with a vote of 91-1, while the Senate rejected it with a vote of 40-4. The bill will now go into effect in November. All 68 of Stitt’s vetos were on the legislative table for overrides–– 47 were overridden, a new State record.

The Oklahoma House of Representatives overrode the veto on House Bill 1137 91-1, while the Oklahoma Senate rejected it 40-4.

The crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples (MMIP) remains a significant issue in America. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) reports approximately 1,500 American Indian and Alaska Native individuals are missing, with around 2,700 murder and non-negligent homicide cases documented. Altogether, about 4,200 cases are estimated to be unsolved.

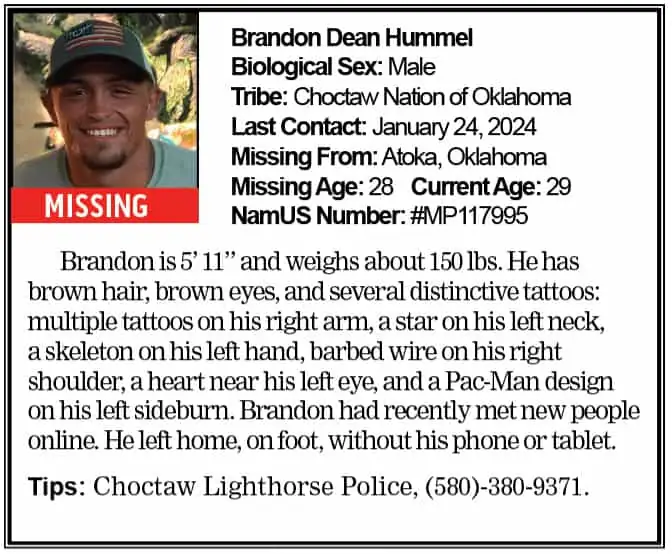

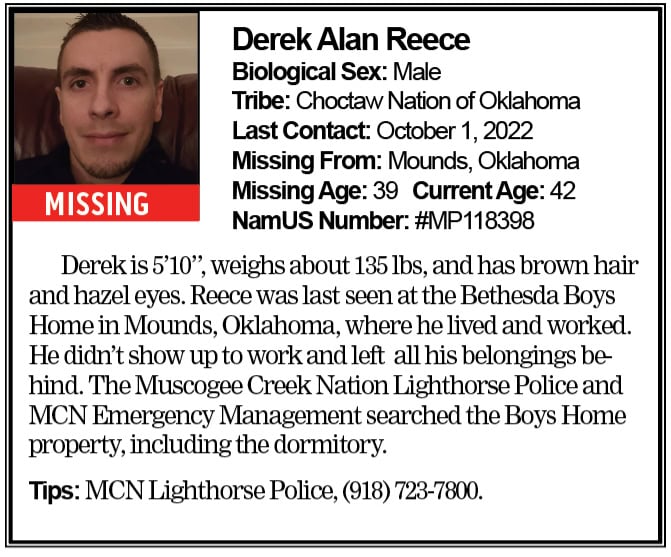

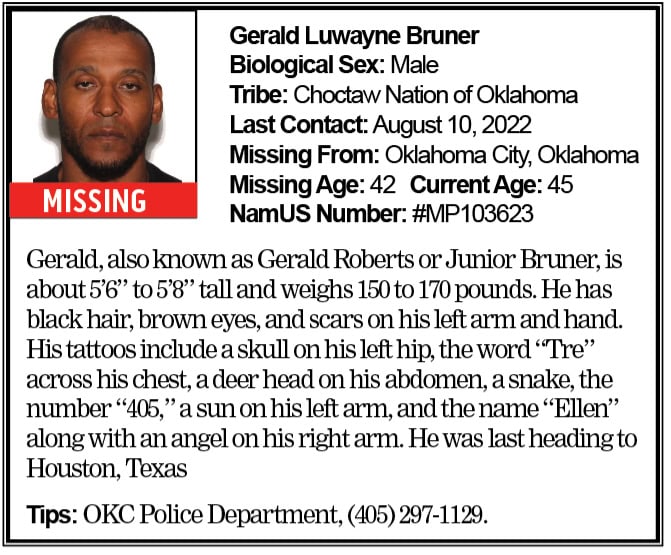

National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs) shows that Oklahoma has the second-highest number of MMIP cases, with 85 members of various tribes currently missing, including Choctaw tribal members Brandon Hummel from Atoka, Derek Reece from Mounds and Gerald Bruner of Oklahoma City.

There are also many unsolved murders, like Choctaw tribal member Emily Morgan, who was murdered outside of a vacant home on East Highway 271 in Bache near McAlester. Thanks to the diligence of her mother, Kim Merryman, Morgan’s case has gotten the attention of the BIA and the Vidocq Society, an elite group of investigators who assist law enforcement with unsolved crimes. Her case has been featured in numerous publications and articles, including NBC’s Dateline’s digital series Dateline: Missing in America and Cold Case Spotlight.

For many MMIP cases, family are their biggest advocates. Across Indigenous cultures, family is a core value, and women are at the center of it all.

Before colonization, Choctaw women accompanied men on diplomatic missions, a practice that, according to a 2011 Iti Fabavssa article, European commentators believed was a mark of “savagery.” From the Choctaw perspective, it was a sign of the importance women held in their society and the confidence that was placed in these women.

Today, women like LaRenda Morgan (Cheyenne Arapaho), who worked with State Rep. Mickey Dollens, D-Oklahoma City, and State Sen. Paul Rosino, R-Oklahoma City, on the legislation that led to Ida’s Law, are standing up not only for their family members but also for all Indigenous people.

Ida’s Law is named after Morgan’s cousin, Ida Beard, who went missing in 2015.

Though Ida’s mother reported her missing almost immediately, the El Reno Police Department took two weeks to open a missing person case. This error cost valuable time in gathering evidence.

Six years after her disappearance, thanks to the diligence of her family and other MMIP activists, Ida’s Law was signed by Governor Stitt in 2021.

Ida’s Law called for the creation of the Office of Liaison for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons within the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation (OSBI).

This office works across jurisdictions, including tribal, to investigate unsolved cases involving Indigenous people and create a case tracking system.

This year, House Bill 1137, related to Ida’s Law, passed both chambers of the Oklahoma legislature with strong bipartisan support. However, on May 5, Governor Kevin Stitt surprisingly vetoed the bill.

In an interview with The Oklahoman, OSBI spokesperson Hunter McKee mentioned that the agency currently has only two special agents working as liaisons for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons (MMIP). While the agency aims to expand the MMIP program, securing federal funding has been challenging. House Bill 1137 would have removed the requirement for the OSBI to seek federal funding for the Office of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons without prohibiting the voluntary use of existing federal mechanisms.

The agency did not expect any budgetary impact from this change.

Stitt’s veto surprised many advocates and legislators, particularly since he had previously signed Ida’s Law and the Kasey Alert System into law.

In the announcement claiming that “Justice must be blind to race,” Stitt stated, “While I support efforts to solve missing persons and homicide cases, I cannot endorse legislation that singles out victims based solely on their race.”

He went on to say, “Creating a separate office that prioritizes cases based on race undermines the principle of equal protection under the law and risks sending the message that some lives are more worthy of government attention than others.”

This statement directly contradicts the governor’s previous statements.

When he initially signed Ida’s Law, Stitt stated, “Far too often, when a Native person goes missing or is found murdered, their families have to navigate a complex checkerboard of jurisdiction. That confusion makes it so difficult on victims’ families during what’s already a traumatic time.”

Stitt’s announcement was released on Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Awareness Day.

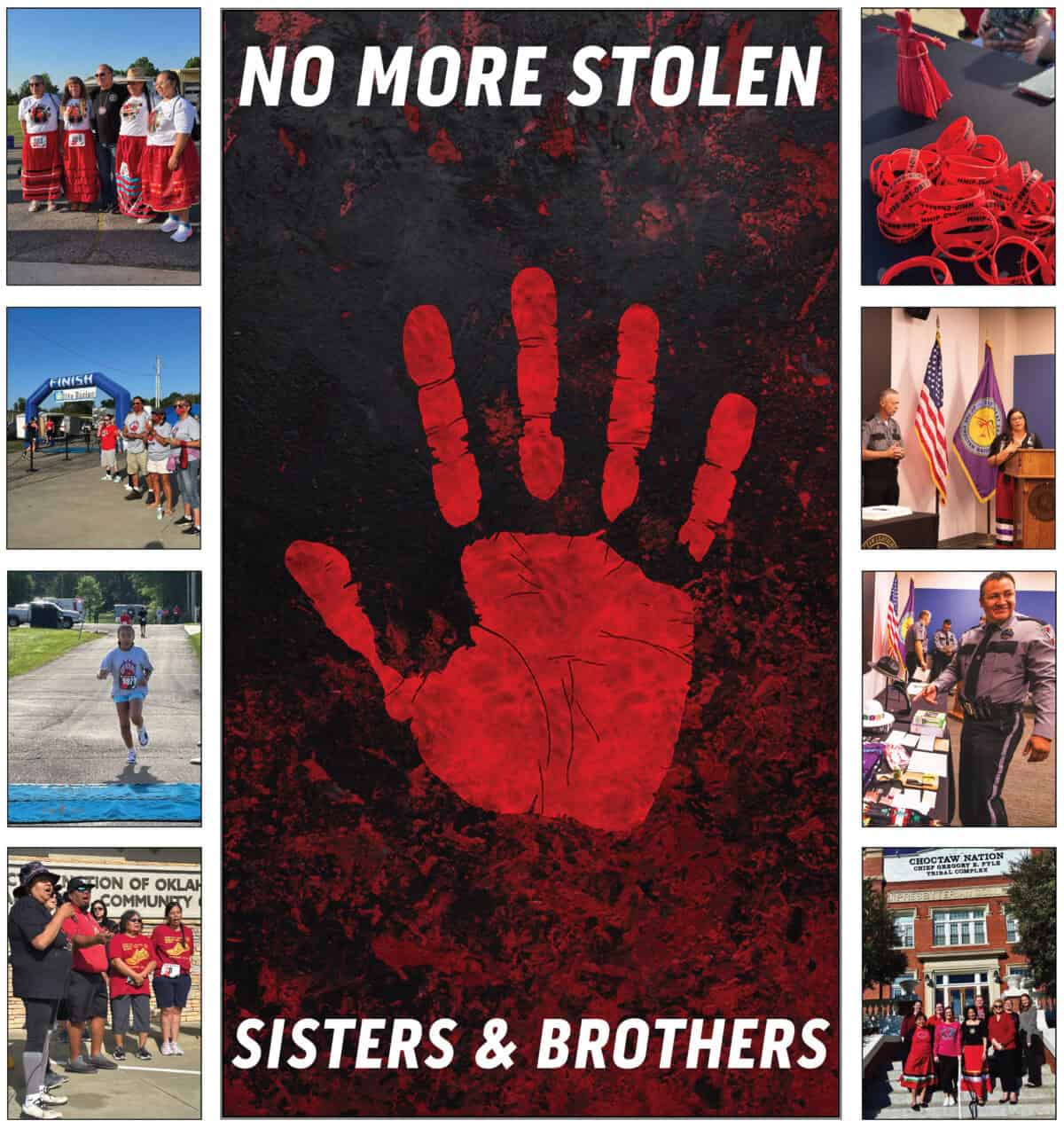

On that day, MMIP advocates and organizations, including MMIW-Chahta, gathered at the capitol to raise awareness of the issue.

Regardless of the actions of Governor Stitt, those gathered at the event were able to bring awareness to the issue.

“It was a beautiful day to be Indigenous at the capitol,” said Karissa Newkirk, founder and president of MMIW-Chahta. “Anytime we stand in solidarity, my heart has a little more hope.”

In an op-ed published by the Oklahoman on May 19, Newkirik stated, “Gov. Stitt’s veto is the latest example of persistent institutional failures that cause untold harm and tragic consequences…As our nation reflects during National Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Month, we must confront the deep-rooted neglect and societal indifference that has perpetuated for centuries. We must keep fighting for those we love and have lost.”

According to Newkirk, MMIW-Chahta has had another year of growth and success, helping the Indigenous Community in Southeastern Oklahoma access vital services and programs.

The organization works to raise awareness of MMIP, directly assists victims in active MMIP and domestic violence situations, and educates the community on MMIP, domestic violence, mental health and healing.

They provide food for the unhoused and furnish homes for those escaping domestic violence through community donations. Additionally, MMIW-Chahta helps victims access tribal services, employment, and life skills training.

“We want them to have access to everything they need to set them up for success,” said Newkirk.

The organization has opened a new office at 723 West Texas Street in Durant, Oklahoma, which includes a clothing closet and public classes and events.

They have launched the Today Support Group, founded by Aaron Newkirk, to help those facing mental health issues and advocate for suicide prevention.

MMIW-Chahta also collaborates with law enforcement agencies on missing and murdered Indigenous persons (MMIP) issues.

On May 14, the group held its second annual law enforcement appreciation banquet in Durant. Local agencies were invited to connect and discuss MMIP matters. Building strong relationships with law enforcement is essential for raising awareness and solving cases, according to Newkirk.

More information on getting involved, donating or utilizing MMIW-Chahta services, is available on their Facebook page, Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women–Chahta, at www.mmiwchahta.org, by calling 888-401-0972, or emailing [email protected].

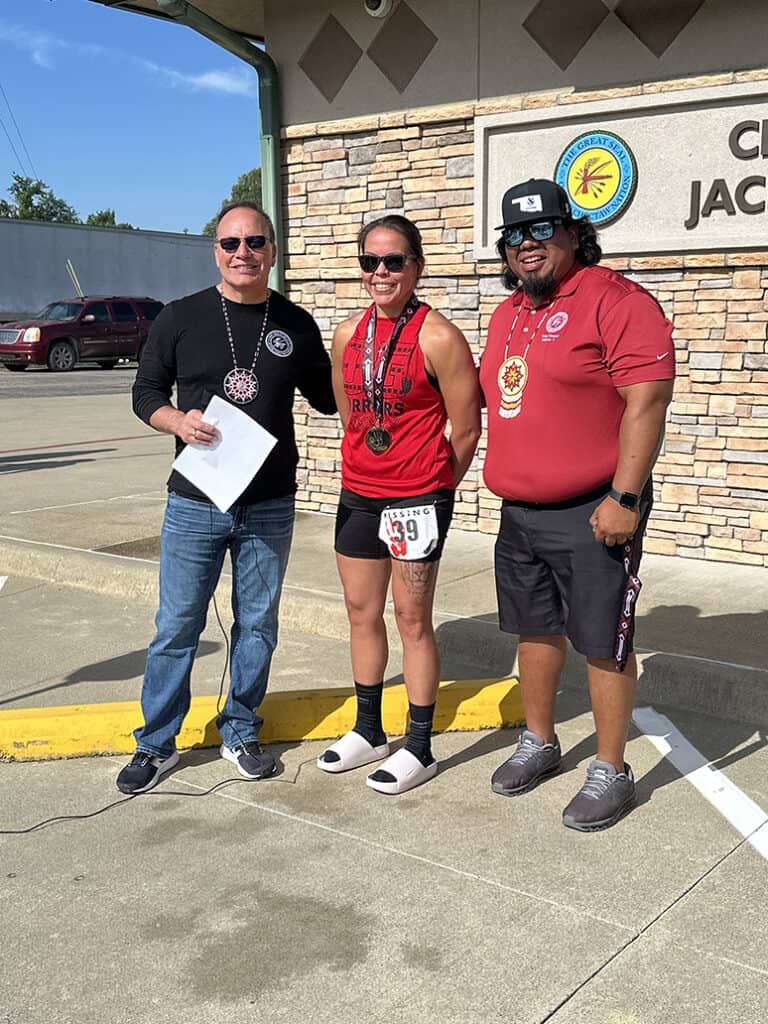

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma also showed support for MMIP awareness through its annual MMIW Walk and 5k in Antlers, Oklahoma on May 10.

The official number of participants was 292, with Nolan Watson of Broken Bow and Tiffany Burchfield of Rattan, taking home the overall first-place medals in the men’s and women’s divisions.

According to the BIA, more than 1.5 million Indigenous people have experienced violence in their lifetime.

CNO offers several programs for victims of crime and abuse and there are many national services available as well.

If you are someone you know is experiencing violence, please reach out to one of the following programs and services for help.

- Family Violence Prevention

Provides quality specialized services and resources that promote family strengths, stability and enhance the safety of victims of domestic violence, family violence or dating violence and their dependents. - Project SERV

A transitional housing program for victims of intimate partner violence who are facing homelessness that services 8 to 12 individuals from a minimum of 6 to a maximum of 24 months. - Tribal Victim Assistance

Provides comprehensive services to victims of crime. Services include emergency food, clothing, shelter, safety planning, goal planning, counseling, court system advocacy and other victim advocacy services. - Behavioral Health

Provides a variety of mental health services for adults, adolescents, and children. - Project EMPOWER

A coordinated system of care that assists victims of domestic violence by helping them stabilize housing, childcare and other day-to-day support so they can focus on reclaiming their lives. - Tribal Victim Services

Guidance for victims of crime and their families with counseling and group therapy. - Juvenile Services

Provides intake, assessment, treatment planning, probation and parole services, supervision as well as reintegration to delinquent tribal juveniles within the Choctaw Nation reservation. - Essential Life Skills

Provides assistance to qualified adult, youth and child victims of all types of crime. - Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner Program (SANE)

A specialized service that provides compassionate and expert care to individuals who have experienced sexual assault or abuse. - Lighthorse Police & Public Safety

Patrols and manages the 10,864 square miles of the reservation through various departments. If you have an emergency call 580-920-7000. For non-emergencies related to public safety, contact 580-920-1517.

National resources include:

- STRONGHEARTS Native Helpline

This helpline offers 24/7 culturally-appropriate support and advocacy to American Indians and Alaska Natives who are victims of domestic and sexual violence. Contact the helpline by phone or text at 844-7NATIVE (844-762-8483) or live chat. - The Tribal Resource Tool

The Tribal Resource Tool is a searchable map of victim service programs for survivors of crime and abuse. The tool was developed by the National Center for Victims of Crime, the National Congress of American Indians, and the Tribal Law and Policy Institute, with funding support from OVC. - BIA Victim Assistance Program

The BIA Office of Justice Services established the victim services program specifically for victims located in Indian country. It was created in part due to unique challenges encountered when crimes occur in Indian country and to help fill the gap between the Federal and tribal court systems. This program offers direct services to victims including crisis intervention, referrals and information for mental and emotional health and other types of specialized responses, provide emergency services and transportation, and follow up for additional assistance