In the November issue of the Biskinik, we discussed how traditional Choctaw beliefs are still practiced by some tribal members despite a strong Christian presence.

According to a 2023 Public Religion Research Institute survey, 63% of Native Americans identify as Christian, most as Protestant. About 7% are non-Christian, 5% affiliate with other non-Christian religions, and 31% identify as nonreligious.

Today, the Choctaw Nation identifies as a Christian nation. Prayers are offered before meals and tribal events, Christian hymns are sung, and tribal members worship together at community gatherings.

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in this story are those of Olin Williams and Les Williston and do not represent the Choctaw Nation as a whole.

In the Beginning

Spanish and French Catholics were the first Christians to contact Native Americans.

Williams said Roman Catholicism was the first form of Christianity introduced to Native people by the Spanish, presenting them with a new type of deity.

He noted that because Catholicism is a monotheistic faith emphasizing the mother-son relationship, it resonated with Native people.

Although the Spanish shared Christian beliefs, they were primarily focused on taking resources. Because of this, and due to distrust, the Choctaws retained their original beliefs.

About 300 years later, the English introduced Protestant Christianity, which emphasized that all people were created equal. Williams said Protestant teachings introduced the concept of the Father and the Son.

He said the English felt God had blessed the Natives with resources, but they believed those resources were not being utilized in ways they considered beneficial. Because of this, the English sought to become a kind of paternal figure to Native people, even calling themselves “the Great White Father in Washington” in treaties.

This attitude created a divide. “While Euro-Americans strived for dominance over the world they lived in, the Native Americans strived to live in harmony with the environment in reverence of living things,” said Williams.

Williams said Europeans interpreted the Bible as teaching that God gave the world for their use, shaping their view of natural resources.

In contrast, Native people venerate all living things and share what has been given to them. Williams gave the following example.

“When they see a tree, they see its value,” said Williams. “It could be a boat. It could be furniture. They see it differently.”

Native people regarded all things as living beings and lived freely, with a shared understanding that what had been given by God was to be shared.

Ceremony and Fellowship

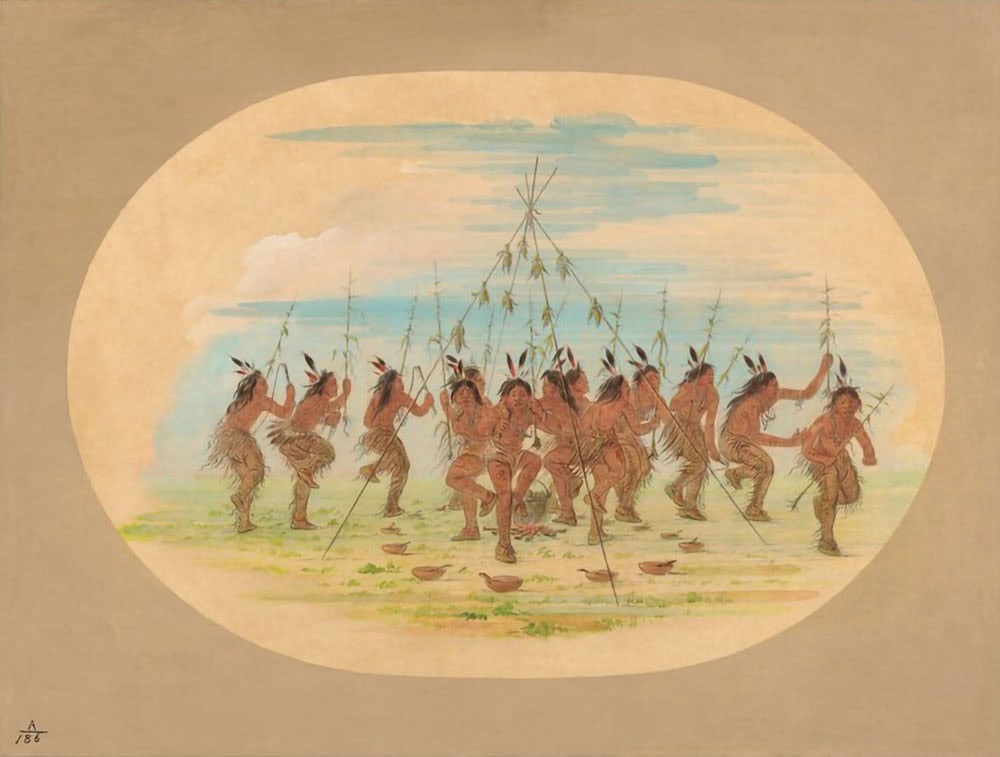

One traditional expression of gratitude is the Green Corn Ceremony, a ceremony that has remained largely unchanged for about 1,000 years.

“When corn first came to the southeast, it was given to us by a deity called the Corn Woman,” said Williston. “After that, the admonition was that we have corn now, and it was given to support our tribe, our families and to feed us. Now it feeds the whole world.”

Traditional ceremonies such as the Green Corn Ceremony and sweat lodges have played a significant role in Choctaw life, with sweat lodges dating back nearly 1,000 years in northeastern Alabama.

A March 2010 Iti Fabvssa article described the Green Corn Ceremony as “the most important social and spiritual event in the traditional seasonal round of the Choctaw and other Tribes.”

Less is known about the Choctaw ceremony compared with other Southeastern tribes because details were considered sacred and many specifics were withheld.

According to a 1937 account by Lucy Cherry, the Green Corn Ceremony began a week earlier with hunting and harvesting and lasted four days. The first day involved setting up camp and sharing food. The second day included fasting and cleansing by the Alikchi, or Choctaw doctor. The fast was broken on the third day, followed by dancing after an opening prayer. The fourth day focused on breaking camp and visiting with family and friends.

Fellowship is central to both Christian church gatherings and traditional ceremonies.

Traditional ceremonies are typically shared through word of mouth.

According to Williston, these events are not promoted publicly, but elders can guide those who ask.

“If you’re a Native, you can find it,” Williston said.

Life After Death

Christian beliefs hold that the afterlife is spent in God’s presence. According to Williston, traditional beliefs also include a next world shaped by how a person lived.

“In Native culture, there’s a next world,” said Williston. “What’s going to happen over there, just might be determined by how you live this world, and that’s how I believe.”

According to Williston, many consider Jesus Christ a European construct created to account for one’s sins, while in Native culture, saving one’s soul is determined by one’s actions.

“Who has the ability to save your soul? That’s you. By your actions. If you’re going to go through life and be a bad person, you’re going to have a bad life. Maybe here, maybe next world,” Williston said. “You’ll be judged.”

Growing in Faith

Williams believes people can combine some of both belief systems but must know which one guides their life.

“I’m a Christian and I minister the Word, but sometimes my flesh wants to go back to watch a good stickball game or a good dance or something. But I know from within when not to let that addict me,” said Williams. “If our tribe keeps going back, we’re going to step behind every time. Our young people, even the church, need to advance.”

He said some churches stay rooted in Old Testament teachings instead of moving toward New Testament ideas about grace.

The New Testament teaches believers to deny self-righteousness and love others by grace.

“It’s the soul that you want God to change, but the law wants to change the outside appearance,” said Williams.

Williams says issues such as homosexuality and race have existed throughout history. However, for him, “it’s how much maturity spiritually we have or how infant we are in our spirituality.”

Williston said each person has a relationship with the Creator, and that relationship develops between the individual and the Creator.

“We’re all born knowing right from wrong,” said Williston. “We’re taught that much. It’s inside of us.”

According to Williston, there are no conservative or liberal divisions in traditional belief, and “ not a lot of difference between the traditional belief systems across this country.”

Similarities in Beliefs

When asked whether he sees similarities between traditional religion and Christianity, Williams said, “I think everything is similar because we’re trying to have a deity.”

According to Williams, it is human nature to seek a greater power.

“We’re a people of need and affection, and that’s when religion came. We need to feel accepted, to feel there is a higher power,” said Williams. “That’s why all races, all cultures have some kind of religion.”

According to Williston, Christianity incorporates elements of Indigenous societies.

“They’ve taken part of the Indigenous society there and parts of their beliefs and put it into their Christianity to form a big system that will draw more people in,” said Williston.

As the beliefs and practices of Choctaws continue to evolve and differ from person to person, there remains more to learn for those who wish to explore.

Readers can find more information about Choctaws and religion by visiting the Iti Fabvssa section of biskinik.com. To hear traditional Choctaw ceremonial songs, visit www.biskinik.com.

One Choctaw version of the Great Flood

February 1996 BISHINIK, page 7

One Choctaw version of the Great Flood is as follows:

In the far distant ages of the past, the people, whom the Great Spirit had created, became so wicked that he resolved to sweep them all from the earth, except Oklatabashih (People’s mourner) and his family, who alone did that which was good. He told Oklatabashih to build a large boat into which he should go with his family and also to take into the boat a male and female of all the animals living upon the earth.

He did as he was commanded by the Great Spirit. But as he went out in the forest to bring in the birds, he was unable to catch a pair of biskinik (sapsuckers), fitukhak (yellow hammers), and bakbak (large red-headed woodpeckers); these birds were so quick in hopping around from one side to the other of the trees upon which they clung with their sharp and strong claws, that Oklatabashih found it was impossible for him to catch them, and therefore he gave up the chase, and returned to the boat; the door closed, the rain began to fall increasing in volume for many days and nights, until thousands of people and animals perished.

Then it suddenly ceased and utter darkness covered the face of the earth for a long time, while the people and animals that still survived grouped here and there in the fearful gloom. Suddenly far in the distant north was seen a long streak of light. They believed that, amid the raging elements and the impenetrable darkness that covered the earth, the sun had lost its way and was rising in the north. All the surviving people rushed toward the seemingly rising sun, though utterly bewildered, not knowing or caring what they did. They saw, in utter despair, that it was but the mocking light that foretold how near the Oka falama was at hand, rolling like mountains on mountains piled and engulfing everything in its resistless course. All earth was at once overwhelmed in the mighty return of waters, except the great boat which, by the guidance of the Great Spirit, rode safely upon the rolling and dashing waves that covered the earth. During many moons the boat floated safely o’er the vast sea of waters.

Finally Oklatabashih sent a dove to see if any dry land could be found. She soon returned with her beak full of grass, which she had gathered from a desert island. Oklatabashih, to reward her for her discovery, mingled a little salt in her food. Soon after this the waters subsided and the dry land appeared: then the inmates of the great boat went forth to repeople another earth. But the dove, having acquired a taste for salt during her stay in the boat continued its use by finding it at the salt-licks that then abounded in many places, to which the cattle and deer also frequently resorted.

Every day after eating, she visited a salt-lick to eat a little salt to aid her digestion, which in the course of time became habitual and thus was transmitted to her offspring. In the course of years, she became a grand-mother, and took great delight in feeding and caring for her grandchildren. One day, however, after having eaten some grass seed, she unfortunately forgot to eat a little salt as usual. For this neglect, the Great Spirit punished her and her descendants by forbidding them forever the use of salt.

When she returned home that evening, her grandchildren, as usual, began to coo for their supply of salt, but their grandmother having been forbidden to give them any more, they cooed in vain. From that day to this, in memory of this lost privilege, the doves everywhere on the return of spring, still continue their cooing for salt, which they will never again be permitted to eat. Such is the ancient tradition to the Choctaws of the origin of the cooing of doves.

But the fate of the three birds who eluded capture by Oklatabashih, their tradition states: They flew high in the air at the approach of Oka falama, and as the waters rose higher and

higher, they also flew higher above the surging waves. Finally, the waters rose in near proximity to the sky, upon which they lit as their last hope (perching upside down upon the sky). Soon, to their great joy and comfort, the waters ceased to rise, and commenced to recede. But while sitting on the sky, their tails, projecting downward, were continually being drenched by the dashing spray of the surging waters below, and thus the end of their tail feathers became forked and notched, and this peculiar shape of the tails of the biskinik, fitukhak and bakbak has been transmitted to their latest posterity.

But the sagacity and skill manifested by these birds in eluding the grasp of Oklatabashih, so greatly delighted the Great Spirit that he appointed them to be forever guardian birds of the red men. Therefore these birds, and especially the biskinik, often made their appearance in their villages on the eve of a ball play; and whichever one of the three came, it twittered in happy tones its feelings of joy in anticipation of the near approach of the Choctaws’ favorite game.

But in time of war, one of these birds always appeared in the camp of a war party, to give them warning of approaching danger, by its constant chirping and hurried flitting from place to place around their camp. In many ways did these birds prove their love for and friendship to the red man, and he ever cherished them as the loved birds of his race, the remembered gift of the Great Spirit in the fateful days of the mighty Oka falama,

From: Choctaw Social and Ceremonial Life, pages 204-205.